-

Washington Western Bluebird Reintroduction Effort a Success!

Western Bluebird Babies by-Lauren-Ross (Washington, D.C. , August 11, 2011) A five-year cooperative effort involving several organizations has succeeded in returning the Western Bluebird to Washington’s San Juan Islands. The bird had historically inhabited the islands, but changing land use practices and a paucity of nesting sites meant the species had not nested there for over 40 years.

Over the course of the five-year project, biologists with the Western Bluebird Reintroduction Project captured and translocated 45 breeding pairs of Western Bluebirds from an expanding population at Fort Lewis Military installation, Washington, and another four pairs from the Willamette Valley in Oregon. The birds were kept in aviaries on San Juan Island prior to release to acclimate them to their new surroundings.

One pair of translocated birds nested in the first year, and in each succeeding year the nesting population size has increased. Over the five years, 212 fledglings were produced. Most encouragingly, some of those fledged birds have returned each year and are now part of the breeding population, giving hope that the population will be able to sustain itself into the future.

“It is gratifying to have the hard work of so many people bear fruit with the result that we now see these birds coming back to an area they had once called home. This year, the islands are home to 15 breeding pairs of Western Bluebirds that fledged 74 birds,” said Bob Altman, project leader with American Bird Conservancy. “We are very optimistic about the future of this population,” he said.

The project collaborators included American Bird Conservancy, Fort Lewis Military Installation, Ecostudies Institute, San Juan Preservation Trust, San Juan Islands Audubon Society, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and The Nature Conservancy of Washington.

Thirty birds returned to the San Juan Islands this year. Ten were translocated birds from previous years, 18 were fledged from previous years, and two were of undetermined origin. The 15 pairs of birds built 25 nests, of which 14 were successful.

“This year saw record breaking cool, wet weather through June, meaning everything, including bluebird nesting, was about three to four weeks behind. This resulted in reduced productivity from the previous year. House Sparrows also caused three or four nesting failures, which is something we may need to address in coming years,” Altman said.

The project is now moving into a two-year monitoring phase to determine the stability and growth of the population, and the need for future population management.

“We are very pleased to have achieved our goal of establishing a breeding population, however, 15 pairs is by no means a large enough population to be considered secure, so we are exploring ways to enhance it beyond the initial five-year period,” he said.

One potential enhancement is Western Bluebird translocations in nearby British Columbia that may be starting next year. The San Juan Islands are only 20-25 miles as the bluebird flies from the proposed release site on Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, and it is likely that the continuation of translocations in British Columbia will help to sustain the San Juan Islands population in the future.

In tandem with the translocations, project partners also are working to conserve the oak-prairie ecosystem that the birds depend on. Toward that end, the San Juan Preservation Trust made a key prairie-oak land acquisition – 120 acres in the center of the San Juan Valley- which hosts two nesting pairs of bluebirds and is a primary location at which flocks of bluebirds congregate during the post-breeding season. In addition, approximately 600 nest boxes have been put up on the islands to provide additional nesting opportunities for the returning birds.

Altman said that “the project would not have been possible without the help of numerous people on the San Juan Islands, who hosted aviaries and nest boxes on their properties, helped construct nest boxes and move aviaries, provided materials and project equipment, and helped monitor nest boxes and look for released birds. Further, he added “I don’t know of any other bird reintroduction project that relied completely on so many private landowners”.

-

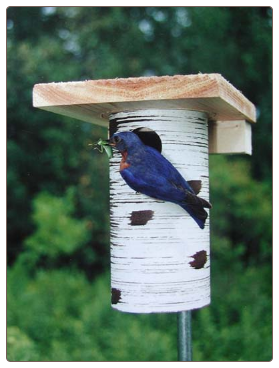

blue bird houses vacant?

Using recycled materials greatly helps the environment by reducing waste and keeping said materials out of landfills. It takes about 25 to 40 plastic milk jugs to produce a recycled bird house or feeder. These blue bird houses are NABS approved, (North American Bluebird Society) and create the perfect nesting site for Eastern Bluebirds. With such a large shortage of natural nesting cavities, why would a great nest site like this be vacant?

Several factors will deem successful habitat for birds, and pesticides are detrimental in successful clutches. Environment plays the biggest role in attracting birds, and while everything may be super green and manicured in your yard, it may not be good for your avian friends. Ingested through insects fed by adults, pesticides wreak havoc on developing nestlings. Although sometimes not harmful to the adults, they are deadly to nestlings. If clutches in an area repeatedly fail, the bluebirds are likely to abandon the spot and seek other habitat.

Predators will also discourage nesting. Roaming cats, raccoons, snakes and larger bully birds will drive bluebirds from a possible nest site. House Sparrows and Starlings (both non-native species) will kill adult bluebirds in the nest box, as well as nestlings, and even destroy eggs too. Unfortunately this is common practice. These invasive and destructive birds are likely the main cause for the bluebird’s demise in the 70’s and 80’s. Ever-shrinking natural habitat with fierce competition for available nest sites being the reason.

•Be sure that blue bird houses are erected in proper habitat. Open spaces are preferred, with perching spots for hunting insects.

•Predator guards on bluebird houses also increase chances of successful fledging.

•Keep roaming cats indoors, or ask your neighbor to keep their cat out of your yard.

•Fresh water will entice bluebirds and others.

•Remove old nests (away from the area) after birds have fledged. A blue bird house with an old nest will not be used by another pair of bluebirds seeking a nest box.

•Supplemental feeding (with live mealworms) helps parents raise their young.

•Absolutely… quit the pesticides.

-

bluebird houses and turf wars

Is it possible to have too many bluebird houses? The answer would be yes and no, depending on several factors and just how “into” bluebirds you’re willing to get. I recently joined a forum for Bluebird Monitors as I’ve seen some pretty bizarre happenings with bluebirds this season.

In the past, Eastern Bluebirds have over-wintered in our North Georgia Yard, and have gone on to nest in various bluebird houses, raising several successful broods. It’s awesome to watch older siblings help raise the fledgelings too. And mom and dad will work as a pair for about 30 days to raise their brood.

The first five eggs all hatched, all fledged… off to a good start, right? Not really 🙁 The male disappeared about 3 days before these babies fledged, so mom was on her own. It wasn’t long before these babies learned to feed themselves at the mealworm feeder. Granted, only three of them made it thus far, but it looked promising. I then noticed a strange lump, almost a protrusion on one of these babies, which was the reason for joining the bluebird forum. After posting the question, I’d received a detailed answer saying this was likely a broken air sac, which happens frequently to fledgeling as they can’t really tell yet what’s solid or open. It could either absorb itself, or turn infectious. I watched daily, this group of three siblings who stuck together at feeding times. It was the female with injury and I so hoped she remain okay. And she did for a while, until the turf wars began.

Enter a new male Eastern Bluebird: he had it in for these fledgelings as they were not his brood. Relentlessly he’d chase them from feeder to feeder, dive-bombing and harassing them constantly. It was the most difficult thing to watch. The new male was trying to attract one of the two adult females… and with all his might at that. One day there were no fledgelings, two days and no fledgelings, by day three I’d given up. The male had either driven them from the area, or killed them. I’d never seen Bluebirds engage in such behavior, and it saddened me.

About one week later, I learned of the new nest and the babies who had hatched. Never actually monitoring this bluebird house, I’d watch the female cram as many worms in her mouth as she could and fly to the box, so I knew she was feeding hatchlings. This bluebird house sits very high up, so again, it was never monitored. The ot

her day I saw both parent bring three fledgeling to the mealworm feeder, and had better hopes for a successful brood.

Typically Bluebird Houses should be about 100 feet apart. With an acre of land, we have several different kinds of houses for them. Other cavity nesters also use bluebird houses and this is where some extreme bird wars are created. House Sparrows are enemy number one, destructive and aggressive, they’ll chuck Bluebird eggs from the houses, kill nestlings, and even adult Bluebirds. House Wrens will do the same, wreaking havoc on Bluebirds. Tree Swallows will also compete for Bluebird Houses, and sometimes adding a second house 10-15 feet apart helps eliminate competition. After reading the many posts from the Bluebirds Forum, I’ve learned that most species are quite territorial during nesting season, aggressive and downright mean. Predator guards help some, and devices called “sparrow spookers” may keep these non-native demons at bay, but I guess it’s just survival of the fittest, kinda sad that mother nature can be so tough.