-

FOX SPIT HELPED FOREST SERVICE CONFIRM RARE FIND

Photo taken by Keith Slausen The Humboldt-Toiyabe’s spectacular 6.3 million acres makes it the largest national forest in the lower 48 states. Located in Nevada and a small portion of eastern California, the Forest offers year-round recreation of all types.

University of California, Davis

September 3, 2010Three weeks ago, when U.S. Forest Service biologists thought they had

found a supposedly extinct fox in the mountains of central

California, they turned to UC Davis for confirmation.Photographs taken by a Forest Service trail camera near Sonora Pass

seemed to show a Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) biting

a bait bag of chicken scraps. That would be an amazing discovery,

since no sighting of that species has been verified south of Mount

Lassen, 200 miles away, since the mid-1990s.The biologists shipped the bait bag to wildlife genetics researchers

Ben Sacks and Mark Statham at the UC Davis Veterinary Genetics

Laboratory. Since 2006, they have radically altered our understanding

of red foxes in California, supplying information crucial to

conservation efforts.Sacks and Statham scraped saliva from the tooth punctures on the bag

and analyzed the DNA within. Before you could say spit, they had the

answer: definitely a Sierra Nevada red fox.“This is the most exciting animal discovery we have had in California

since the wolverine in the Sierra two years ago — only this time,

the unexpected critter turned out to be home-grown, which is truly

big news,” Sacks said. (The wolverine was an immigrant from Wyoming.)Four years ago, Sacks began analyzing California red fox DNA

collected from scat, hair and saliva from live animals, and skin and

bones from museum specimens. Until then, the expert consensus was

that any red fox in the Central Valley and coastal regions of the

state was a descendant of Eastern red foxes (V.v. fulva) brought here

in the 1860s for hunting and fur farms.Sacks and his colleagues have confirmed that red fox populations in

coastal lowlands, the San Joaquin Valley and Southern California were

indeed introduced from the eastern United States (and Alaska). But

they have also shown that:* There are native California red foxes still living in the

Sierra Nevada.

* The native red foxes in the Sacramento Valley (V.v. patwin) are

a subspecies genetically distinct from those in the Sierra.

* The two native California subspecies, along with Rocky Mountain

and Cascade red foxes (V.v. macroura and V. v. cascadensis), formed a

single large western population until the end of the last ice age,

when the three mountain subspecies followed receding glaciers up to

mountaintops, leaving the Sacramento Valley red fox isolated at low

elevation.Sacks’ extensive research program focuses on canids, especially red

foxes (evolution, ecology and conservation) and dogs (genetics,

geographic origins and spread). He and his students also are working

on other carnivores, including disease ecology and interactions among

fishers, bobcats, coyotes and gray foxes, and population genetics of

ringtails and coyotes.About UC Davis:

For more than 100 years, UC Davis has engaged in teaching, research

and public service that matter to California and transform the world.

Located close to the state capital, UC Davis has 32,000 students, an

annual research budget that exceeds $600 million, a comprehensive

health system and 13 specialized research centers. The university

offers interdisciplinary graduate study and more than 100

undergraduate majors in four colleges — Agricultural and

Environmental Sciences, Biological Sciences, Engineering, and Letters

and Science. It also houses six professional schools — Education,

Law, Management, Medicine, Veterinary Medicine and the Betty Irene

Moore School of Nursing.Additional information:

* Ben Sacks home page, including a place to report fox sightings <http://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/cdcg/home.php>

* U.S. Forest Service news release on Sierra Nevada red fox discovery <http://www.fs.fed.us/r4/htnf/>Media contact(s):

* Ben Sacks, School of Veterinary Medicine, (530) 754-9088,

[email protected]

* Sylvia Wright, UC Davis News Service, (530) 752-7704,

[email protected] -

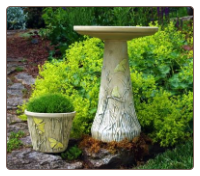

Bird Baths Handcrafted the Old Fashioned Way

Want to entice more feathered friends? Better than any birdhouse or bird feeder, bird baths really do the trick. Fresh water is very appealing to many species, even those who may never visit a feeder or use a birdhouse.The water element is in fact the most crucial one when creating a wildlife habitat.

If you fancy the nicer things in your garden, there are pedestal type bird baths that are still crafted the old fashioned way by talented artisans. Fine clays are used to create elegant designs, many are even hand painted. The Best Friends Bird Bath shown at left features an intricate relief of cats and dogs. The character is charming, and you can be sure birds will love it too! With a patented locking lid system for added stability, this bath will last for many seasons of use.

Although the production methods differ significantly they share certain features – an emphasis on quality, craftsmanship, and attention to detail, offering beautiful, American-made bird baths and garden decor.

-

Bluebird Houses in the News: Proven Beneficial

It’s difficult to convince folks sometimes, and all the blogging in the world may not make a bit of difference. But when the Associated Press does an article on the benefits of backyard birding…it seems a bit more substantial. Bluebird houses have been proven beneficial in the fight against unwanted insects. Much better than ineffective pesticides, most of which have been rendered useless….read on!

DEAN FOSDICK

This Jan. 23, 2005 photo shows an Eastern bluebird photographed near McLeansville, N.C. Eastern bluebirds are voracious insect feeders, especially during nesting and rearing periods. Their primary diet includes flies, katydids, beetles, worms and spiders. They’re aerialists, catching insects on the fly or pouncing on them on the ground. (AP Photo/Dean Fosdick)

Growers are beginning to understand that common birds can be of uncommon value to fields, lawns and gardens.

Many avian species earn their keep by eating insects and small mammals, and destroying weed seeds.

“Commercial growers are turning to birds as an alternative or supplement to pesticides,” said Marion Murray, an Integrated Pest Management project leader with Utah State University Cooperative Extension. “But you have to have the environment or habitat before inviting them in.”

That means mimicking nature by providing plenty of food, water and cover. Put up some bluebird boxes or nest boxes for raptors, said Marne Titchenell, a wildlife specialist with Ohio State University Extension.

“Monitor the bluebird boxes so sparrows don’t take over,” she said. “Brushier habitat provides protection for insect-eating songbirds. Allow the edges of your woodlot to grow up a bit. Berry-producing shrubs are excellent things to have around for all kinds of wildlife.”

Birds occupy a unique place in nature, according to the authors of a timeless 1912 study, “Red Bird, Green Bird: How Birds Help Us Grow Healthy Gardens,” by Harry A. Gossard and Scott G. Harry (Ohio State University Extension, revised edition 2009). “Each species performs a service which no other can so well accomplish,” the authors said.

Raptors such as hawks and owls chase down field mice, moles and grasshoppers. Insectivores like bluebirds, chickadees and woodpeckers stalk beetles, worms and grubs.

Meadowlarks are ground feeders, favoring meadows and farm fields where they gorge on grasshoppers and weevils. Robins focus on lawns and gardens, where they pull up cutworms, wireworms and other larvae injurious to crops.

Chickadees are birds of the forest, eating tent caterpillars, bark beetles and plant lice. Goldfinches prefer open country where they can pursue caterpillars and flies. “No other bird destroys so many thistle seeds,” the authors say.

“An individual tree swallow, barn swallow, purple martin or chimney swift can eat up to a thousand flying insects a day,” said David Bonter, assistant director of Citizen Science with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “They can have a big impact.”

While it’s great to have these specialized bug hunters around if you’re a grain farmer, small commercial farmer or orchard grower, recruiting should be directed toward a variety of species, said Margaret Brittingham, a professor of wildlife resources at Penn State University.

“All insect eaters feed at different heights, on different plants and prefer different insects,” she said. “Having some (bird) diversity is important in maintaining insect populations. What we don’t want to wind up with is having a monoculture with birds as we frequently do with plants, inviting problems.”

___

Online:

For more about birds for alternative pest management, see this Utah State University fact sheet http://utahpests.usu.edu/htm/utah-pests-news/fall-09/

You can contact Dean Fosdick at deanfosdick(at)netscape.net

This Jan. 23, 2005 photo shows an Eastern bluebird photographed near McLeansville, N.C. Eastern bluebirds are voracious insect feeders, especially during nesting and rearing periods. Their primary diet includes flies, katydids, beetles, worms and spiders. They’re aerialists, catching insects on the fly or pouncing on them on the ground. (AP Photo/Dean Fosdick)

This Jan. 23, 2005 photo shows an Eastern bluebird photographed near McLeansville, N.C. Eastern bluebirds are voracious insect feeders, especially during nesting and rearing periods. Their primary diet includes flies, katydids, beetles, worms and spiders. They’re aerialists, catching insects on the fly or pouncing on them on the ground. (AP Photo/Dean Fosdick)